Frederick Calkins, Master’s Mate

by Joseph Ross

“Man that is born of a woman is of few days and full of trouble. He cometh forth like a flower, and is cut down: he fleeth also as a shadow, and continueth not.” 1 The ancient wisdom literature of the biblical Job captures the essence of the brevity and finality of mortality common to all men of every faith. Everyman must face the shared reality that the evidence of one’s life quickly evaporates with death. A man’s place in history is largely limited to three short generations. A generation of deeds and contemporaries, a generation of children who remember the man and some of his deeds well and finally, a generation of children’s children who remember little and only vaguely the man and his footprints in time and space. Rarely does the world take note of a man’s life beyond the scraps of paper that gather dust in dark attics and inaccessible vaults of public record rooms and research libraries. To such a fate most are destined; excepted only kings and generals, captains and commanders whose fits and feats fill the pages of our schoolbooks. History often written in words of self-promotion and inordinate attention to the few. Acta Non Verba, motto of the United States Merchant Marine Academy, summarizes another perspective of history. A story told through observation and critical examination of “deeds, not words.” A favorite high school English teacher was fond of suggesting only “kooks and queerish people write history, normal folk are too busy living life to write about it!”

So it is for Frederick Calkins. Born to an age full of trouble. Known to us only through the writings of both those who loved him and others who felt nothing especially toward him. In the documents of his life, particularly the Revolutionary War pension records authored decades after his death; we observe the details of Frederick Calkins’ life.I In the details of his life, the evidence of his presence, is a story worth telling. Worth remembering. A mariner’s story.

We met Frederick Calkins in the roster of the sloop Dolphin, one of twenty-six Connecticut Ships-of-War to serve in the American Revolution. Our acquaintance began with the acquisition of an invoice for four pounds eleven shillings dated 12 May 1778 in Norwich for nine days work on mast repairs to the Dolphin by one Isaac Palmer. The eighty-ton ten-gun sloop sailing out of British-occupied Newport was a prize of the fifty-ton four-gun schooner Spy commanded by the daring Captain Robert Niles. She was captured off Long Island on 10 September 1777. Purchased at auction by the State of Connecticut shortly thereafter on 29 November, Niles was appointed her master. Frederick Calkins, Mate is listed among nine others of “Master Nile’s Men,” serving on the Dolphin from 12 October 1777 to 25 February 1778.2 And so began our search for one man’s footprints in an age of colossal challenge and consequential change.

The oldest of son of Mary Prentiss (or Prentice) and William Calkins, Frederick Calkins was born on Saturday 14 January 1749 in New London, Connecticut.II His twenty-two year old mother was the daughter of Phebe Harris Crank and the late Stephen Prentiss, Jr. of New London. Mary was married to Frederick’s father less than three years before on 20 May 1746 in the “old style.” His twenty-four year old father William Calkins, also born in New London, was the son of Joseph Calkins and Lucretia Turner of Norwich.III

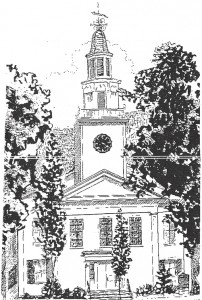

The announcement of their impending wedding is recorded in the diary of Joshua Hempstead 3 of New London, “Sund 4 (May 1746) Rainy Day. Mr Chauncey of Boston pr in ye foren & Mr Taylor of Melton aftern. I was at meeting all day. Wm Caulking & Mary Prentiss publisht.”IV The Calkins’ family history in the Norwich community went back generations beyond Frederick’s father and grandfather to great-grandfather David and to his great-great grandfather Hugh, one of the “Welsh Company” to settle this area in the late seventeenth century. Hugh Calkins, patriarch of the Calkins clan in America, emigrated from Chepstow in Wales with a large congregation following their minister the Reverend Richard Blinman. They first traveled to Mansfield, then to Gloucester in 1642 and finally to New London in 1650. Blinman’s pulpit would eventually pass in 1724 to Eliphalet Adams (1708-1753), called “the father of all the Indian Missionary work done in this area.”4 While founding the Indian schools at Lyme and Groton and serving as trustee of Yale from 1720-1740, Adams presided over “a happy revival” in the New London church.

Frederick Calkins’ father William, the second of ten children, was baptized at two months old on 28 June 1724 with four others by Eliphalet Adams in the same year of his calling to the First Church of New London. His baptism is also recorded in the Hempstead diary, “Sund 28 (June 1724) fair. Mr ad. pr al day. 5 Boys Babtized Ja Rogers Junrs, Lemuel, Jno Lamberts. Thos ; William Dixons William. Jo. Caulk- ings Wm. Will Minors Son Joseph one Daniel.”5 Frederick’s mother Mary Prentiss was also baptized by Eliphalet Adams just two years later on 10 July 1726.6 Eliphalet Adam’s long ministry at this church ending with his death in 1753, has been characterized as an “even-keeled” passage through the emotional storm of the Great Awakening which culminated with the 6 March 1743 “burning of the books” at the head of Hallam Street in New London. Four years after his death, great-grandson of Increase Mather, Mather Byles Jr. (1734-1814) succeeded Eliphalet Adams to the pulpit of the Calkins’ family church. Reverend Mather Byles Sr. of Boston delivered the sermon to the congregation of 160 at his son’s ordination and installation on 18 November 1757. Although the Harvard educated Byles is described as a talented and “eloquent preacher” like his father, the situation in the church at the time is painted as “very bleak.”7 In the interim between pastorates services were conducted by deacons, neighboring ministers and William Adams, eldest son of the late pastor. However, the pulpit is described as “oftener vacant”.8 Perhaps for this reason no records of infant baptisms can be found for the older Calkins siblings- Frederick, Phebe, John Prentiss or Hannah- in the lists of either Adams or Byles. Most certainly, it was during this time that young Frederick would develop his earliest memories in the church.

When Frederick was just thirteen years old, his thirty-eight year old father William Calkins died on Sunday 31 October 1762 leaving a pregnant mother of five months widowed and in the care of six young children. It is difficult to imagine the impact of this death on the large family, particularly on the oldest son Frederick. The circumstances of his untimely passing, as well as, the details of his life remain shrouded in historical darkness. Probate records dated 14 December 1762 value William’s estate at just over eighty-four pounds lawful money. An inventory itemizes the many of the Calkins’ household belongings including: “1 old felt hat, 1 large looking glass, 1 old trunk, 1 old Chest, 1 Gun, 1 Bible, 1 Chest of Drawers Partly finished.” Also included are “17 acres of Land with Buildings thereon” valued at fifty-one pounds. Both the inventory and probate records are signed by the thirty-six year old widow Mary Calkins’ younger brother Stephen Prentiss.9

“served his time before he was of age a number of years with one Capt Carew of Norwich Landing and was trained up to the sea faring business and that he followed the sea until he was 39 or 40 years old.” [Roger Huntington] V

Presumably with the advice of her thrice-married mother Phebe Harris Edgerton, Mary Calkins and her brother Stephen Prentiss of New LondonVI acting as guardian, arranged for the apprenticeship of Frederick Calkins as a mariner to Stephen’s brother-in-law, thirty-two year old Captain Simeon Carew of Norwich Landing.VII Frederick was indentured at age fourteen on Monday 25 April 1763 to serve until his twenty-first birthday.10 In executing the contract, young Frederick bound himself “of his own free Will and Accord… to learn the Art, Trade or Mystery of Navigation.” The Prentiss and Calkins families were well acquainted with the Carew family even beyond the relationship between Frederick’s Uncle Stephen and his master. Simeon’s younger brother Captain Joseph CarewVIII was to be married to Eunice Edgerton, daughter of Frederick’s maternal grandmother Phebe and Lieutenant John Edgerton II just two years after the youngster’s apprenticeship commenced. Frederick’s beloved grandmother would not live to celebrate the marriage however, as she died on 29 July 1763 and was buried in Old Norwich Town Cemetery just three months after young Frederick went to work at sea for Captain Carew. The loss of her husband and mother within ten months must have been almost too much for the grieving widow Mary Prentiss Calkins to bear. It would be another five years before the mariner’s mother was to remarry to Simon Gager on 6 August 1767 when Frederick Calkins was eighteen years old. It was the second marriage for both as Simon Gager had lost his former wife of twenty-five years Sarah Manwaring just four months earlier. Mary Calkins Gager would bear her eighth child Mary, Simon Gager’s first child, three years later on 16 June 1770.11

“my late husband Frederick Calkins commenced a seafaring life when he was 14 or 15 years old … and that when he was in the Sea Service he was always a cabin boy when he was young and afterwards Mate and Captains Mate.” [Annis Calkins]

Frederick’s seafaring life began like many mariners of the day- as cabin boy. The position of cabin boy had long been the starting point of a trajectory of military and merchant sea service. Too young and inexperienced for midshipman or seaman duties, the cabin boy worked long hours acting as a servant for the ship officers- passing messages, running errands, caring for clothes, serving meals and even serving the crew as “beer drawer”. He was expected to learn all duties of a sailor, often under strict discipline, as he was groomed for a position of eventual shipboard authority. In this regard, Frederick Calkins’ training conformed to the traditional model for English maritime training employed for centuries; like Sir Francis Drake who two hundred years earlier was taken onboard at fifteen, working his way up to captain’s mate at the age of twenty-five. It also paralleled that of notable contemporaries like Stephen Girard who started as cabin boy on his father’s French ships at age fourteen, making first mate nine years later at age twenty-three and John Paul Jones who also began as an apprentice mariner, indentured for seven years to English merchant John Younger. Jones became first mate at nineteen years old and was chief mate on a slaving ship when he completed his apprenticeship at age twenty-one in 1768. Leaving the “abominable trade”, Paul Jones as he was known at the time, was appointed master the following year. It is not likely the physical duties of cabin boy presented any special difficulties for Frederick Calkins as he and his brother John Prentiss Calkins, were both noted for their “muscular ability.”12 It is equally unlikely that the young Calkins experienced the kind of abuse that some apprentice mariners experienced at the hand of a cruel master. Daniel Vickers in Young Men and the Sea: Yankee Seafarers in the Age of Sail recounts how Calkins’ contemporary Ashley Bowen “was whipped with the ‘cat’ by Boston Captain Peter Hall for dirtying his master’s towel while scouring down the aftercabin.”13

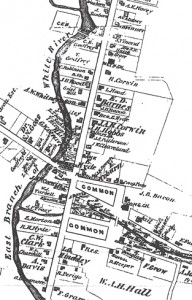

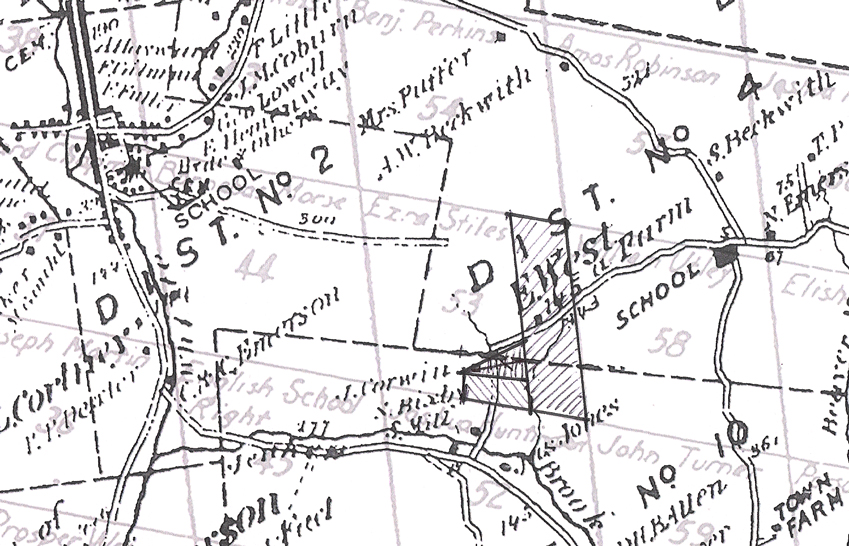

Frederick Calkins would have received an excellent mariner’s training under Captain Carew at Norwich Landing. Now known as Norwich and formerly as Chelsea, Norwich Landing is located at the convergence of the Shetucket and Yantic Rivers where they form the Thames River in Connecticut. A local center of commerce, sloops and freight boats were regularly sailing the Thames as early as 1753. “In 1731, Gov. Joseph Talcott reported that in the entire colony, there were 44 trading vessels that had a total capacity of 456 tons. By the eve of the Revolutionary War, the number of vessels had quadrupled and their total tonnage multiplied by twenty-fold.”14 Frederick Calkins’ earliest seafaring experience was gained on the sloop Eagle under Captain Carew as she traveled between Norwich and “Greene’s Wharff” in Boston.15 Two years into his apprenticeship, newspaper records indicate the ship was advertising “to take in Freight for Connecticut” just before she cleared out of Boston Custom House late in April 1765.16 Carew is again reported sailing in and out of Boston from Connecticut the following April.17 Later that year in September 1766, Carew and the sloop Eagle are entered in the New London Custom House from Halifax.18 The following year on 28 September 1767, Simeon Carew and the sloop Exchange were entered into New York from Halifax again.19 Both the Eagle and Exchange were characteristic of the many sloops operating out of Norwich and New London participating in the Coasting and West Indies trades. They were usually single-masted with a long bowsprit and fitted out with a large gaff-rigged mainsail, often a square topsail, and several jibs.20 Typically, the ships were locally built and thirty to seventy tons. “With livestock…transported under awnings above deck, the small vessels were notoriously unsteady.”21 The ships were typically less than seventy feet long, carried a cargo of less than five tons and were manned by a master, mate, two to four seamen and a cabin boy. The crews were not large relative to the size of the ship as merchants deliberately kept overhead costs low. During this time, “carrying the bare minimum of crewmen and stinting on food were standard practices in the merchant marine.”22

Frederick Calkins’ apprenticeship contract required his master to “Covenant and Promise to Teach and Instruct his said Apprentice… in the Art, Trade or Calling of a Mariner” while providing his charge with “Good and Sufficient Meat, Drink, Washing and Lodging.” In order to “Learn him the Art of Navigation,” Captain Carew would have insured that Frederick’s navigation workbook was filled with hand-copied lessons including: Geometrical Problems, Plain Trigonometry, Mariner’s Compass, Plain Sailing, Parallel Sailing, Middle Latitude Sailing, Mercator Sailing, Oblique Trigonometry, Oblique Sailing, Current Sailing, Variation of the Compass, Nautical and Geographical Definitions and Journal Keeping of a Voyage. In addition to mastering such texts as Euclide’s Elements: The Whole 15 Books, Compendiously Demonstrated with Archimedes Theorems of the Sphere and the Cylinder, Frederick Calkins would have been instructed at sea in “all the intricacies of seamanship and ship handling, the proper set and trim of the sails, (and) the uses of all the myriad ropes and spars” that secured and controlled the masts.23 Since it was common for New England sea captains involved in the West Indies trade to make two voyages each year, we can presume that Frederick Calkins made multiple cruises to the West Indies “before the mast” during this time of apprenticeship prior to his posting as mate.IX The fledgling pre-war West Indies trade exporting horses and other livestock, fish, flour, provisions and lumber and returning with imported cargoes of rum, molasses, cotton and sugar would prove to be the training ground for many of the Continental Navy’s young officers. It is also reasonable to assume that the young mariner spent ample time with his family when in port, attending church with other “West-enders” at the New Concord Society in Norwich. At the expiration of his apprenticeship on 25 January 1770 on the occasion of his twenty-first birthday, Captain Simeon Carew was obligated to give Frederick Calkins “Two Good Suits of Apparroll for all Parts of his Body, one for Holy Days, the other for Working Days.”

Certainly it was this good suit for Holy Days that the twenty-three year old Frederick wore to Bozrah Congregational Church on Sunday 3 May 1772, the day he received adult baptism and was administered communion.24 The day was special indeed as his twenty year old sister Phebe and sixteen year old sister Hannah were also baptized and received into the full communion of the church at the same time. As Frederick’s younger siblings Temperance, Elizabeth and William were baptized as young children in the Bozrah Church, only nineteen year brother John Prentiss Calkins had not offered a public profession of his faith in the church.X It is not precisely known when the Calkins family was dismissed from the First Church of New London and began worship at the New Concord Society, subsequently known as the Bozrah Congregational Church. One conjectures that it was probably 1767 when the widow Mary Calkins moved from New London to Norwich to marry West-ender Simon Gager. One year before, in what became known as the Rogerene disturbances, the Calkins’ family church in New London was thrown into great distress. After a decade of service, minister Mather Byles Jr. abruptly quit the call on 12 April 1768 and shortly thereafter boarded a packet boat to Newport. It is interesting to speculate if nineteen year old indentured mariner Frederick Calkins was working aboard the vessel of Byles’ exiting transit. The reverend would travel on to Boston where he eventually became an Episcopalian.

Bozrah, part of both the original “nine miles square” Norwich and the Parish of West Farms, was incorporated in 1786. Bozrah is the name of the Syrian town referred to Micah 2:12 “I will surely assemble, O Jacob, all of thee; I will surely gather the remnant of Israel; I will put them together as the sheep of Bozrah, as the flock in the midst of their fold: they shall make great noise by reason of the multitude of men.” The congregational church at Bozrah or Norwich Plains was first organized in 1733 and called West Society. By the 1760’s it was known as the New Concord Society or the Fourth Society of Norwich. Frederick Calkins’ minister at Bozrah was the Reverend Benjamin Throop (1712-1785). Ordained and installed at the New Concord Society in 1738, Throop also served as Chaplain to the Crown Point Expedition of 3,500 British and colonials against the French at Fort St. Frederic in 1755. Throop was pastor when Calkins experienced the spiritual awakening that would define his Christian faith for the balance of his life. Sometime between when he “owned the covenant” earlier at New Concord and his baptism and acceptance into full communion in May 1772, Frederick Calkins came to experience a personal faith in Jesus Christ.25 While it is impossible to know precisely when and how he met the carpenter who could walk on water and command the winds and waves, one can imagine that it may have been on the deck of Carew’s sloop in the midst of a West Indies hurricane or North Atlantic gale. Merchant mariners like Frederick Calkins are whom the psalmist writes of, “They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; These see the works of the LORD, and his wonders in the deep. For he commandeth, and raiseth the stormy wind, which lifteth up the waves thereof. They mount up to the heaven, they go down again to the depths: their soul is melted because of trouble. They reel to and fro, and stagger like a drunken man, and are at their wit’s end. Then they cry unto the LORD in their trouble, and he bringeth them out of their distresses. He maketh the storm a calm, so that the waves thereof are still. Then are they glad because they be quiet; so he bringeth them unto their desired haven. Oh that men would praise the LORD for his goodness, and for his wonderful works to the children of men! Let them exalt him also in the congregation of the people, and praise him in the assembly of the elders.” 26

The statement of faith Calkins earlier “owned” was the controversial Halfway Covenant, “I do heartily take and avouch this one God who is made known to us in the Scripture by the name of God the Father, and God the Son even Jesus Christ, and God the Holy Ghost to be my God, according to the tenor of the Covenant of Grace; Wherein he hath promised to be a God to the Faithful and their seed after them in their Generations, and taketh them to be his People, and therefore unfeighnedly repenting of all my sins, I do give up myself wholly unto this God to believe in, love, serve and Obey Him sincerely and faithfully according to this written word, against all the temptations of the Devil, the World, and my own flesh and this unto death. I do also consent to be a Member of this particular Church, promising to continue steadfastly in fellowship with it, in the public Worship of God, to submit to the Order, Discipline and Government of Christ in it, and to the Ministerial teaching, guidance and oversight of the Elders of it, and to the brotherly watch of Fellow Members: and all this according to God’s Word, and by the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ enabling me thereunto. Amen.”XI To the twenty-first century ear, the Halfway Covenant reads as a perfectly acceptable even conservative statement of faith. However, to the generation of Frederick Calkins it represented an intellectual adherence to traditional religious doctrine that lacked expression or evidence of personal experiential faith. Full membership and the administration of the sacraments including adult baptism and the Lord’s Supper were reserved only for those free of scandal, orthodox in belief and who willingly offered public testimony of spiritual regeneration. No doubt, the entire Calkins and Gager families were present for Frederick Calkins’ profession of faith two weeks after Easter Sunday 1772. It is likely his betrothed Annis Huntington who grew up in the “Great Plains” of Bozrah also witnessed this solemn service as they would be married just seven months later. Annis too would “own the covenant” the following year on Thanksgiving Thursday 25 November 1773 at the First Congregational Church of Norwich, just two months after the birth of their first child.XII

“that a short time before we were married he studied navigation one winter at Norwich Landing” [Annis Calkins]

Between the completion of his apprenticeship in January of 1770 and his marriage to Annis Huntington almost three years later in December 1772, it is fair to assume that Frederick Calkins made several additional West Indies voyages as mate or even master. He would have served on many shorter cruises if he was working one of the coastal trade ships or packet boats. Liverpool and Halifax, Nova Scotia were other common destinations for the Norwich and New London sea captains where some, like Seth Harding, maintained second homes. His wife indicates that just before their marriage in 1772, Calkins received some advanced training in navigation. This time of concentrated study was common to the process of advancing towards command of a ship. While we are not privy to the precise date of Frederick Calkins’ promotion and posting to position of mate, it is certain that he would have been tested by examination and granted the rate by either Captain Carew at sea by a local board of experienced peers ashore. No doubt during this time, the young bachelor was aspiring to his own command and accumulating the means to prepare for marriage and the setting up his own household. A tantalizing newspaper article suggests that during the seven months between his communion ceremony in May and his marriage ceremony in December 1772, Frederick Calkins shipped out on an ill-fated cruise to the West Indies as master of an unnamed schooner. Upon his arrival in New York on 26 September 1772, Captain Jeremiah Harris reported the effects of “a most violent Hurricane…which drove several Vessels from their Anchors, three of whom were lost” at St. Martins one month earlier in late August. The three ships included “a Schooner, Caulkins, Master of Norwich, in Connecticut.”27

The extent of devastation generated by this storm was recorded in a published letter from seventeen year old Alexander Hamilton to his father, “I take up my pen just to give you an imperfect account of one of the most dreadful Hurricanes that memory or any records whatever can trace, which happened here on the 31st ultimo at night. It began about dusk, at North, and raged very violently till ten o’clock. Then ensued a sudden and unexpected interval, which lasted about an hour. Meanwhile the wind was shifted round to the South West point, from whence it returned with redoubled fury and continued so ’till near three o’clock in the morning. Good God! what horror and destruction. Its impossible for me to describe or you to form any idea of it. It seemed as if a total dissolution of nature was taking place. The roaring of the sea and wind, fiery meteors flying about it in the air, the prodigious glare of almost perpetual lighting, the crash of falling houses, and the ear-piercing shrieks of the distressed, were sufficient to strike astonishment into Angels. A great part of the buildings throughout the Island are levelled to the ground, almost all the rest very much shattered; several persons killed and numbers utterly ruined; whole families running about the streets, unknowing where to find a place of shelter; the sick exposed to the keeness of water and air without a bed to lie upon, or a dry covering to their bodies; and our harbors entirely bare. In a word, misery, in all its most hideous shapes, spread over the whole face of the country.”28

One can’t help but wonder if Frederick Calkins returned to Norwich to find himself one of the many Norwich ship officers shifting in the pews of the First Congregational Church, the Huntington family church, on Sunday 27 September 1772 as the Reverend Benjamin Lord delivered his sermon from the Gospel of Matthew on ‘The parable of the merchant-man seeking goodly pearls.’XIII ”Again, the kingdom of heaven is like unto treasure hid in a field; the which when a man hath found, he hideth, and for joy thereof goeth and selleth all that he hath, and buyeth that field. Again, the kingdom of heaven is like unto a merchant man, seeking goodly pearls: Who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had, and bought it.”29 For a young mariner in the merchant service, this gospel message hits particularly home. It’s easy to project that the metaphor of the one-of-a-kind pearl applied as much to the beautiful young woman Annis Huntington sitting closely by as much as it applied to the Kingdom of Heaven. It seems probable that Frederick was introduced to the prospect of marriage to Annis during long watch conversations on the quarterdeck with his master Captain Simeon Carew, whose cousin Captain Eliphalet Carew had married Annis’ older sister Mary Huntington ten years before in 1762.XIV It was well understood by both shipowners and captains that mates who were married proved to be the most reliable and productive officers, a valuable commodity with so great an investment in the ship, cargo and provisioning of each merchant cruise.30

Just two months after the memorable sermon, twenty-three year old Frederick Calkins was married to seventeen year old Annis Huntington by the venerable Reverend Lord on Wednesday 2 December 1772 in the same Norwich church.31 Her dear younger brother Roger attended the wedding, presumably with all of Annis’ seven older siblings and her parents, James Huntington and his wife Elizabeth Darby. Because of Annis’ age, the marriage would have required her parents explicit consent. Also attending the wedding would have been Annis’ favorite eight year old niece Susannah Huntington, daughter of the brides’ oldest brother William Huntington and Annie Pride. No doubt the wedding celebration included the traditional games, singing, dancing and plenty of food like beef, venison and pork. Perhaps at the celebration, one of Frederick’s sisters Phebe or Hannah selected the special piece of cake with nutmeg inside which signaled who was next to marry.32 The “earnest evangelical preacher” Benjamin Lord must have enjoyed particular satisfaction in marrying the young Calkins, whose relative Hugh Calkins with his wife Phebe had promoted a Separatist schism in Dr. Lord’s congregation twenty-seven years earlier. By the time of Frederick and Annis’ wedding, the Reverend Benjamin Lord had celebrated the jubilee year of his Norwich ministry, establishing a reputation as a “conservative in the wave of the New Light excitement” known as the Great Awakening.33 The inscription on Dr. Lord’s gravestone still sermonizes across the generations in favor of religious rationality and intellect over emotional fervor with the epitaph “Think Christians, Think.” Frederick and his new bride however, were thinking more about things of the heart. Within a month, Annis was pregnant with their first child Phebe named for Frederick’s mother and sister, born Thursday 2 September 1773.34 The age in which the young newlyweds started their family was bearing other children, the Sons of Liberty. Since the Stamp Act of 1765 was enacted when Frederick was sixteen years old, the community of Norwich “seemed to be thoroughly imbued with the spirit of freedom…”35

Frederick Calkins came of age in a historic time of revolutionary change. “Until the close of the war for independence, almost every patriotic measure adopted was an act of the town, not of impromptu assemblages of the friends of liberty or of committees. Like those of Boston, the people of Norwich had their Liberty Tree, under which public meetings were held in opposition to the Stamp Act. The repeal of the Stamp Act was celebrated, on the first anniversary of the event, on the 18th of March, 1767, with great festivity, under Liberty Tree, which was decked with standards and appropriate devices, and crowned with a Phrygian cap. A tent, or booth, was erected under it, called a pavilion. Here, almost daily, people assembled to hear news and encourage each other in the determination to resist every kind of oppression…”36 It seems likely that the twenty-five year old Frederick Calkins, if not at sea on a trading voyage to the West Indies or Halifax at the time, would have attended the 6 June 1774 Norwich town meeting to consider “the melancholy state of affairs” and to appoint a standing Committee of Correspondence. Just three months later on Sunday 3 September, in response to an erroneous report of a British massacre of Bostonians, 464 local men were organized at the Liberty Tree under Major John Durkee to come to their aid. The following year, the Norwich community responded to the Lexington Alarm in a similar manner with Frederick’s twenty-two year old younger brother John Prentiss Calkins among them. It was during this time almost two years after the birth of Frederick Calkins’ first child, as the winds of war whipped all around the young family, a second daughter Elizabeth, named in honor of his wife Annis’ mother and older sister, was born on Saturday 13 May 1775.37

“I have no knowledge or belief that he served as a common sailor but he and others who were out in the Sea Service with him always called him Mate … and that he had the command when the Captain was sick or disabled which was several times and that he always stated that he was second in command and that this officer was called the Mate of the vessel or Captains Mate. “ [Annis Calkins]

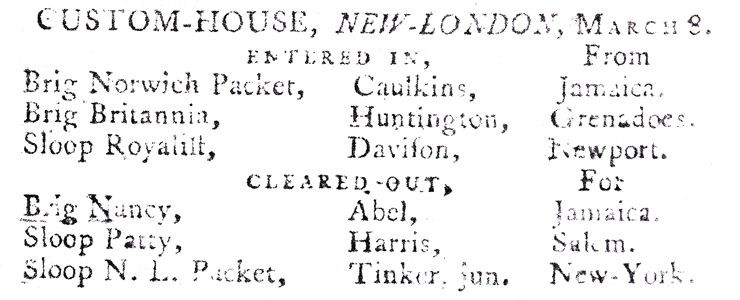

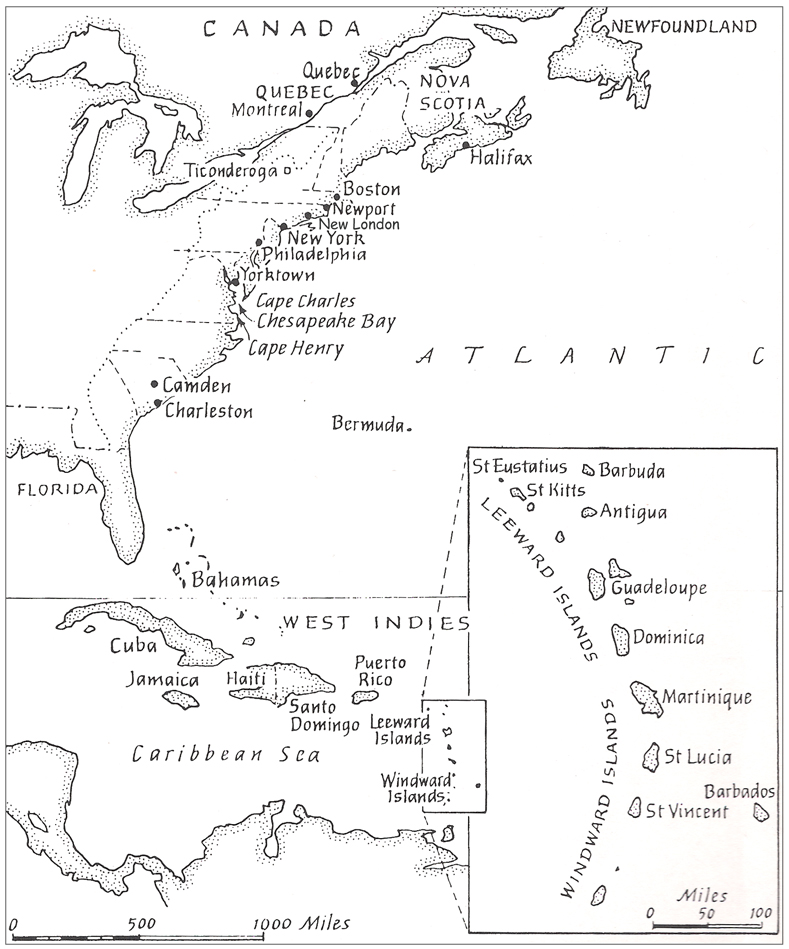

For almost seven and a half years after the completion of his apprenticeship, we know little of Frederick Calkins’ career in the maritimes except that he served as mate aboard ship. The position of mate was the bridge an ordinary seaman had to cross if he aspired ever to be shipmaster. Daniel Vickers in Young Men and the Sea: Yankee Seafarers in the Age of Sail reminds us that upward mobility through this position was not only possible, but common. Using a study of Salem mariners sailing out of the South River between 1745 and 1759, Vickers reveals that almost half of all mariners reached mate and over a quarter became master. Adjusting for those who died during mid-career, illustrative of the danger associated with a life at sea, 70% of Salem seamen surviving to longevity advanced to mate and almost 40% became shipmasters.38 Research in British West Indies shipping records to date has shed no light on Calkins’ pre-Revolutionary sea service.XV The loss of New London customs records predating the war demands an exhaustive search of all shipping documents associated with potential ports of call.XVI Pre-war destinations commonly “touched” by New England sea captains include: Antigua, Barbuda, Barbadoes, St. Kitts or St. Christopher’s, Dominico or Domenica, Grenada, Demeria, Nevis, St. Vincent, Montserrat, St. Croix, Saba, St. Eustatius, Martinique, Guadeloupe or Guadalupe and Surinam. One tantalizing clue as to Frederick Calkins merchant career may be found in the Norwich Packet newspaper of 9 March 1775. The published shipping list for the ships entering New London for the previous day includes the brig Norwich Packet sailing under Caulkins from Jamaica. The shipping records for Jamaica have not yet been scrutinized, however, the two other Calkins sailing out of this port in the era seem less likely candidates.XVII

Whenever the crew of a merchant ship exceeded four or five men, a mate would be employed to relieve the master or captain, as several seamen would be on duty at any given time twenty-four hours a day. The master and mate would supervise alternating watches. Larger ships required a sailing master and additional second and third mates to assist in the management of the crew and work. Typically on those larger ships, the captain and sailing master would not be assigned specific watches but rather assumed the freedom and responsibility of executive management over all watches. Successively, each mate accepted responsibility for the operation of the vessel during his four-hour long tenure as “duty officer” or “mate of the watch.”39 Eighteenth Century shipboard life was regulated by six watches each day. Each four-hour watch was further divided into eight increments measured by the “turning of the glass,” a thirty minute hourglass, and marked by the ringing of the ship’s bell. Hence, eight bells signaled the officer and crew shift change that came with the completion of every watch and the commencement of another. To ensure that the same sailors weren’t always on duty at the same time on successive days, the 4 pm to 8 pm watch was further subdivided into a pair of two-hour watches known as the first and second “dogwatch.” Sailors associate this watch with the short and restless sleep called “dog sleep.” Typically, a ship’s crew was divided into three watch groups, thereby insuring that one third of the crew was standing watch at all times. Another third of the crew would be ‘on duty’ performing shipboard work as directed by the standing orders of the day with the final third at rest. The two daily work watches for each third of the crew would be scheduled so that most of the crew was performing shipboard duties during daylight hours. Of course during battle, emergencies and while loading or unloading in port, “all hands on deck” would be the order of the day.

Whenever the crew of a merchant ship exceeded four or five men, a mate would be employed to relieve the master or captain, as several seamen would be on duty at any given time twenty-four hours a day. The master and mate would supervise alternating watches. Larger ships required a sailing master and additional second and third mates to assist in the management of the crew and work. Typically on those larger ships, the captain and sailing master would not be assigned specific watches but rather assumed the freedom and responsibility of executive management over all watches. Successively, each mate accepted responsibility for the operation of the vessel during his four-hour long tenure as “duty officer” or “mate of the watch.”39 Eighteenth Century shipboard life was regulated by six watches each day. Each four-hour watch was further divided into eight increments measured by the “turning of the glass,” a thirty minute hourglass, and marked by the ringing of the ship’s bell. Hence, eight bells signaled the officer and crew shift change that came with the completion of every watch and the commencement of another. To ensure that the same sailors weren’t always on duty at the same time on successive days, the 4 pm to 8 pm watch was further subdivided into a pair of two-hour watches known as the first and second “dogwatch.” Sailors associate this watch with the short and restless sleep called “dog sleep.” Typically, a ship’s crew was divided into three watch groups, thereby insuring that one third of the crew was standing watch at all times. Another third of the crew would be ‘on duty’ performing shipboard work as directed by the standing orders of the day with the final third at rest. The two daily work watches for each third of the crew would be scheduled so that most of the crew was performing shipboard duties during daylight hours. Of course during battle, emergencies and while loading or unloading in port, “all hands on deck” would be the order of the day.

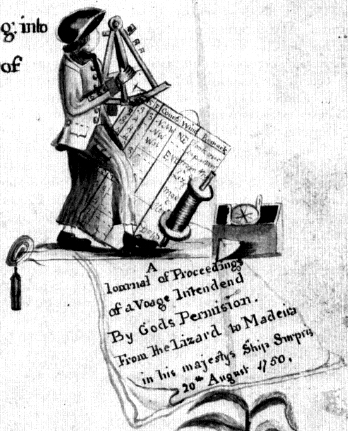

Just before the “afternoon watch” from noon until four, the master and mate would meet together on the ship’s quarterdeck with quadrant or octant in hand to take successive “shots” of the sun until it reached it’s zenith. At that precise moment, the master would call “mark” and the ship’s half-hour glass would be turned, resetting and correcting the ship’s time to local noon, or meridian. The master and mate would then retire to the captain’s cabin to compare readings of the sun’s altitude, make necessary mathematical corrections and plot the latitude on the chart in use as a horizontal line. Charts are simply maps of the sea and shoreline overlaid with the latitude and longitude grid developed by Dutch cartographer Gerardus Mercator in the 16th Century. Often they also note prominent land features, water depths, currents and underwater dangers like shoals and wrecks. Once the daily latitude was “charted,” the ship’s approximate location would be estimated by determining the longitude through “deduced reckoning,” not a precise science in Calkins’ time.XVIII The master would plot the various courses of the previous day using the speed, the course or compass bearing and time of course changes recorded in the ship’s log from the previous day. The plotting of these vectors would ideally intersect with the line of latitude at the location of the vessel at noon, the beginning of every day at sea. A typical log entry would read like that taken for Thursday 20 April 1780 from the journal of Captain of Marines Joseph Hardy of the Continental Ship Confederacy, “Lattitude by Observation at Meridian 36 38” N.- Longt. 72 22” W.- Cape Hatteras S. 69 15” W. distance 206 Miles. Cape Henlopen N. 40 58 Wt. Distance 175 Miles.”40 The importance of precise timekeeping and the limitations imposed by cloudy or stormy weather accentuated the importance of experience accumulated during previous voyages. Like his contemporaries Stephen Girard and John Paul Jones, Frederick Calkins’ distinction from the common sailor was his training in navigation and proficiency with the quadrant, octant or sextant. Most likely, Calkins’ own instrument would have been the “Hadley quadrant,” eighteen to twenty inches long and made of African mahogany or ebony with engraved ivory scale and nameplate with a brass index arm, horizon mirror and backsight mirror enabling him to sight on a celestial object using the opposite horizon should the first be obscured. Technically an octant because its arc was one eighth of a circle, the name was often applied to both large instruments produced prior to 1780.

Master’s mate observing with a Hadley quadrant.

On the ground, left to right, lead and line, log reel with line leading to log ship, and azimuth compass. The log board has the standard headings: H[our]; K[nots]; F[athoms]; Course; Wind; Remark. From the manuscript “A book of Drafts and Remarks . . by Archibald Hamilton, late master’s mate, of his majesty’s ship St Ann. 1763” [Navigation and Astronomy in the Voyages by Derek Howse]

“The position of master or first or second mate aboard a merchantman may not have been nearly so grand as that of a naval officer, but it was better than ordinary seaman, in part because the first or second mate was rarely required to work aloft or heave on a rope.”41 In addition to providing an avenue of upward mobility for a mariner like Frederick Calkins, the professional distinction earned by achieving the rank or “posting the rate” of first mate afforded the officer privileges not shared by other lesser mates. The nautical saying, “a man doesn’t get his hands out of the tar by becoming second-mate” refers to an age of sail when the second mate was still expected to work with the tarpot and “Jack Tar,” slang for the common sailor who wore overalls made of tar-impregnated fabric called tarpaulin. The first mate was exempt from such “dirty work.” The mate was also often accorded ‘privilege’ in addition to his wages. Privilege is the right of portage or the shipowners’ practice of allowing the master and select crew members available cargo space for a specified type and quantity of merchandise free of freight charges. Freight being the “mother of wages” on the high seas, this practice permitted officers an opportunity to share in the success of a merchant voyage by creating a vested interest in the safety of the ship and cargo.42 In addition, it encouraged loyalty among valued crew who used privilege to boost family income while at sea. “On the waterfront, as everywhere in New England, marriage signaled the beginning of an economic partnership, and a prudent wife who was able to manage affairs on her own could take upon herself the business of processing and marketing the goods that her seafaring husband brought home.”43

“Frederick Calkins … was also on board the Trumbull. This declarent believes that if there is in the department records or rolls of the ships above named that the name of her said husband Frederick Calkins will be found as Mate in all three of said vessels and probably others as he was often transferred from one ship to another.” [John W. Smith, Judge of Probate]

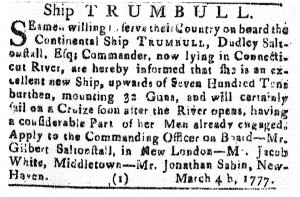

In 1776, the Continental Congress ordered two frigates of 36 and 28 guns each built in Connecticut for the fledgling Continental Navy. Captain Dudley Saltonstall (1738-1796) was appointed to command one of the ships authorized by Connecticut Governor Trumbull and the Committee of Council, subsequently known as the Council of Safety, in mid February 1777. It was to be constructed on the Connecticut River at Chatham under the supervision of Captain John Cotton of Middletown. It is likely that the twenty-eight year old Frederick Calkins answered the call to man the Continental Ship Trumbull advertised in the Connecticut Journal on 12 March 1777, enlisting with Captain of Marines and brother to the ship’s captain Gilbert Saltonstall in New London. Perhaps his enlistment was inked at Nathan Douglass’ Public Tavern at the sign of the Golden Ball opposite the Post Office, a favorite recruitment site for mariners. Frederick Calkins likely served on the Trumbull between early April 1777 when many other enlistments on the ship commenced until shortly before his service on the sloop Dolphin beginning 12 October 1777. While it is not entirely clear why Calkins might have chosen this particular time to enlist in the new national Navy, it is certain that mercantile trade with the British West Indies had come to a complete halt by this time. Trade with the French, Dutch, Danes and Spanish was increasingly dangerous with British warships and privateers keeping American merchant shipping in check. In January 1775, the British Navy included 270 ships with only 24 stationed in North America. By the end of the war in 1783, the number of ships in the British Navy had almost doubled to 478.44 Interesting fact:civilwarthosesurnames.blogspot.com In 1776 our Navy consisted of 90 officers and 3,000 enlisted personnel with only a few jobs above the ordinary seaman level. The Navy is smaller than a single Carrier in 2004. “This deponent declares he has not, nor ever had in his possession a Commission or warrant as Midshipman, it being as he believes the uniform custom in the American Revolutionary service, not to grant such warrants or Commissions to Midshipman, but to enter them on the books and papers of the ship only.” Samuel Buffum S. 12352

“I well recollect he was on board the ship Trumbull rigging and fitting her for sea. I should think in 1777” [Roger Huntington]

Interestingly, Calkins’ name does not appear on the only published roll of the Trumbull from the period.XIX On that crew list, the rate of master’s first mate is the only position with no name listed, a question mark in its place.45 That Frederick was often transferred by orders from ship to ship, suggests Calkins may have been ordered to fill this vacant position rather than enlisting to serve on this particular vessel. As an experienced mate, Calkins possessed the necessary expertise for properly “rigging and fitting her for sea” during this later stage of construction. Work was substantially completed on the ship only after Calkins’ likely departure in late September or early October 1778 just before he reported for duty on the sloop Dolphin. We know that Frederick Calkins visited his wife and family at least briefly during this time between postings as demonstrated by the birth of his third child nine months later. The finished Frigate Trumbull remained in the Connecticut River for yet an additional year, unable to depart due to the ‘Saybrooke Barr’ at the mouth of the river. It wasn’t until 11 August 1779 that she “went over the bar” with the help of floated casks. The Trumbull was then taken to New London for further preparations where Captain James Nicholson of Pennsylvania took command on 20 September 1780, Captain Dudley Saltonstall having been transferred to the Warren. Not until 17 April 1780 were cruising orders issued to Nicholson and the Trumbull actually saw service.

Interestingly, Calkins’ name does not appear on the only published roll of the Trumbull from the period.XIX On that crew list, the rate of master’s first mate is the only position with no name listed, a question mark in its place.45 That Frederick was often transferred by orders from ship to ship, suggests Calkins may have been ordered to fill this vacant position rather than enlisting to serve on this particular vessel. As an experienced mate, Calkins possessed the necessary expertise for properly “rigging and fitting her for sea” during this later stage of construction. Work was substantially completed on the ship only after Calkins’ likely departure in late September or early October 1778 just before he reported for duty on the sloop Dolphin. We know that Frederick Calkins visited his wife and family at least briefly during this time between postings as demonstrated by the birth of his third child nine months later. The finished Frigate Trumbull remained in the Connecticut River for yet an additional year, unable to depart due to the ‘Saybrooke Barr’ at the mouth of the river. It wasn’t until 11 August 1779 that she “went over the bar” with the help of floated casks. The Trumbull was then taken to New London for further preparations where Captain James Nicholson of Pennsylvania took command on 20 September 1780, Captain Dudley Saltonstall having been transferred to the Warren. Not until 17 April 1780 were cruising orders issued to Nicholson and the Trumbull actually saw service.

MASTER NILES’ MEN. 46

Sloop Dolphin to Robert Niles Dr for Sundry Persons Wages by him Paid Viz

Robert Niles Master from Sep. 27 to Mar. 6, 1778

Frederick Calkins Mate from Oct. 12 to Feb. 25

Peter Jeffers Capt from Nov. 14 to Mar 2

John Leseur from Oct. 3 to “ 5

John Paterson from Nov. 15 to Feb. 24

Cornelius Savage from Oct 6 to Mar 6

Zefeniah Hatch from Nov. 14 to “ 2

Abner Bebee from “ 13 to “ 2

Joseph Webb from “ 26 to “ 2

James Treet from Dec. 26 to Feb 24

Lawdin Higgins from “ 29 to “ 18

The eighty-ton ten-gun Sloop Dolphin with her cargo of lumber was a prize of the fifty-ton four-gun Schooner Spy, captured off Long Island by Captain Robert Niles on 10 September 1777 and formally purchased at public auction by the State of Connecticut two months later on 29 November 1777. In late September before the state even closed on ownership of the ship through the libel court process for prize ships, the daring Niles was appointed master of the newly acquired Dolphin and charged with supervision of the refitting of the sloop in Norwich which included the replacement of the mast in late 1777.XX Owing to Niles prewar experience in the West Indies trade, the Connecticut government ordered him to sail to the neutral Dutch island of St. Eustatius for the purpose of obtaining much needed wartime supplies on loan.47 It is likely that Frederick Calkins was selected as mate on this cruise by Captain Niles for precisely the same reason as Niles himself, his prewar West Indies experience. Calkins possibly may have even served under his hometown friend Niles before the war either on the brig Norwich Packet or more likely the schooner Minerva owned by Joseph Howland of New London.XXI His availability for service was due to the Trumbull’s inability to put to sea and resultant idling of her crew. Calkins served with the Trumbull from about April of 1777 until orders brought him to the Dolphin in October. Frederick Calkins wages on the Dolphin commenced on Sunday 12 October 1777. Excepting Captain Niles, only John Leseur and Cornelius Savage entered service on the Connecticut Navy ship prior to Frederick Calkins. Receipts for board, meals and work in the Mystic Seaport sloop Dolphin collection suggest that Leseur and Savage along with fellow crew members Abner Bebee, Zefeniah Hatch and carpenter Peter Jeffers were hand-picked by Niles for service on the Dolphin as early as September. Leseur previously shipped under Captain Niles on the Spy for over a year, first as cook and then as seaman, until his discharge on 26 September 1777- one week before his wages began on the Dolphin. Carpenter Peter Jeffers also served under Niles on the Spy from May to 26 September, just before his employment “overhalling said Sloop” sometime in October. Even young Joseph Webb came from the Spy where he served as cabin boy under Niles. Frederick Calkins’ selection as mate for this cruise would also have been a well-considered decision for the ship’s master. Captain Niles’ experienced and trusted former mate on the Spy, Lieutenant Zebediah Smith was unavailable for duty on the Dolphin, having been appointed master of the Spy with Niles new command. While it initially appears odd that Calkins would have been released temporarily from Continental Navy duty for a stint on this Connecticut state vessel, the practice was not uncommon due to the lack of available ships to accommodate experienced officers. Besides, the Dolphin had been designated for special duties of a national interest illustrated by Niles temporary reassignment from his beloved Spy. Supporting the significance of this cruise was the assembly of the Dolphin’s crew and her refitting well before the ship was legally owned by the state. Characteristically, Captain Robert Niles would be called on again later to perform special naval duty by secret Congressional request.

Receipts in the Mystic collection including an invoice for “Victualing Frederick Calkins” for 34 days at two shillings per day submitted by his uncle John KelleyXXII, suggest that the crew took their accommodations on board the Dolphin beginning 18 November 1777. The sloop was loaded with provisions between 12 and 19 November with ballast loaded on the fourteenth. Wharfage fees appear to end on 22 November with the last dated invoice related to her refitting, for the mending of one compass and supplying a new one dated 25 November 1777. Waiting until the close of the hurricane season at the end of November, Captain Robert Niles and his crew of eight on the Dolphin probably sailed with the early tide on Wednesday 26 November 1777, the date of commencement of wages for the ship’s boy Webb. Arriving in St. Eustatius about one month later on or about Christmas Day 1777, the ship and crew docked in Statia as St. Eustastius was known. The men were advanced one month’s wages to purchase necessaries during their short time in port while enjoying the warmer temperatures of the tropical winter. Based on the date of commencement of their wages, as well as the reduced rate, seaman James Treet and the boy Lawdin Higgins likely joined the crew of the Dolphin in Statia for unloading and loading the sloop and the return voyage home. Ironically, while in St. Eustatius on 30 December 1777, Frederick Calkins’ name was recorded in Norwich on the list of men certified to have taken the Oath of Fidelity to the young United States of America.48 Upon arrival in port, presumably Captain Niles made immediate contact with Continental agents Samuel Curson and Isaac Gouvereur, Jr. in order to procure the return cargo.XXIII This small free port island at the northerly end of the Dutch Lesser Antilles of the Leeward Island chain was the richest trading center of the Caribbean, earning its nickname “The Golden Rock.” St. Eustatius is also known as the first foreign territory to officially recognize the flag of the United States flying atop the Andrew Doria commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson on 16 November 1776, almost two years prior to the Dolphin’s arrival. The island was to be seized and sacked three years later on 3 February 1781 by a brutal invasion force led by British Admiral Sir George Rodney and Major General Sir John Vaughan for precisely the reason that Calkins’ sloop was docked, supplying arms and munitions to the Rebellious colonies.49 Rodney wrote to Rear Admiral Sir Peter Parker that “had it not been for that nest of vipers… this infamous island, the American rebellion could not possibly have subsisted.” Also to his wife he wrote, “This rock had done England more harm than all the arms of her most potent enemies.”50 In a twist of fate, British resources dedicated to Rodney’s preoccupation with confiscating the spoils of Statia’s predominantly Jewish merchants permitted French Admiral de Grasse’s fleet to bottle up Lord Cornwallis’ British Army for General Washington’s coup de grace at Yorktown in October 1781.

Embarking for home in mid January 1778 carrying a cargo of sulfur, a key ingredient in the manufacture of gunpowder, the Dolphin likely put first into New London on 18 February 1778, riding the incoming tide of the Thames River between Forts Griswold and Trumbull. The precise arrival and completion of the cruise probably reflected in the last date of wages of the most junior crew member Lawdin Higgins.XXIV Within days of his arrival, Captain Niles was ordered by the state on 26 February to distribute his cargo of five hogshead of sulphur to four waiting parties including; members of the Connecticut Council of Safety William Pitkin and Nathaniel Wales Jr, Inspector of Firearms Isaac Doolittle and Militia Colonel Jedidiah Elderkin, commander of the powder magazine at Windham.51 Niles appeared in Lebanon approximately one month later on 16 March 1778 to formally report on the voyage to Governor Jonathan Trumbull and the Council of Safety. Twenty-nine year old Frederick Calkins left service on the Dolphin promptly upon his return from his cruise on Wednesday 25 February 1778 and likely joined his pregnant wife of about five months. Calkins’ whereabouts are not clear between the end of his tour on the Dolphin in late February and his reporting to the Frigate Raleigh in mid July and it is speculated that he either returned to duty on the Trumbull or participated in a short cruise with Captain John B. Hopkins on the Warren from early March to 23 March 1778. Several other officers of the Trumbull were among the forty or so men transferred to the Warren earlier in January 1778 for this cruise including Marine Captain Gilbert Saltonstall, Surgeon John Crocker and Lieutenant David Phipps, who would reunite later with Calkins on the Raleigh.

Frederick Calkins’ wages for the four month and thirteen day stint on the Dolphin totaled just over forty-four pounds. His pay as mate was ten pounds per month, the same as the ship’s carpenter Peter Jeffers and half of Niles’ twenty. The balance of the crew were paid nine pounds per month except ship’s boy Joseph Webb and the two latecomers Treet and Higgins.52 According to the Rules for the Regulation of the Navy of the United Colonies promulgated by Congress, Frederick Calkins’ pay rate on the Trumbull would have been fifteen dollars per month. Like his Connecticut Navy compensation, the ship’s carpenter would have been paid the same as the mate. The sailing master and lieutenants would have been paid twenty dollars per month while the captain earned thirty-two dollars.53 In one respect it did not matter if Calkins and his shipmates were paid in pounds or dollars as long as the payroll was made in coin specie as the increasing devaluation of paper currency issued by the government resulted in ongoing erosion of purchasing power and naval morale. By 1778, inflation was so bad that one Spanish milled dollar, which at the onset of the war roughly equaled one dollar of currency, was worth seven Continental dollars. By the end of the war one silver dollar was officially valued at forty paper bills and even up to a hundred on the black market, making the mariners’ wages almost worthless.

Annis and Frederick Calkins’ firstborn son and third child, Frederick Junior, was born on Tuesday 30 June 1778 in Norwich.54 At the precise time of the infant’s birth, the elder Calkins’ former commander Captain Robert Niles was traveling from Brest to Paris after a transatlantic crossing in the Spy of just twenty-two days. Upon secret orders of the Continental Congress, Niles was to penetrate the British blockade of France and hand-deliver the first copy of the ratified Treaty of Military and Political Alliance to Benjamin Franklin bringing the French into the war, eventually sealing Cornwallis’ fate at Yorktown.XXV Despite Charles E. Claghorn’s claim on page 47 of Naval Officers of the American Revolution (1988) that Frederick Calkins participated in this historic voyage, there is no evidence that Calkins and the Dolphin’s new commander Zebediah Smith sailed in convoy with Niles and the Spy from Stonington to Brest. The Spy was captured off France on 29 August 1778 during the return voyage and her twice imprisoned captain Robert Niles would not return to Connecticut until July 1779.

”and afterwards was Mate on board the ship Raleigh- and was out on a cruise. Capt Barry, Commander who was afterwards a Commodore- According to my best recollection he entered the service in the Raleigh about the middle of July 1778 and was out in a serious engagement with two British ships- he returned from his service in the Raleigh as near as I can recollect late in the fall of 1778” [Roger Huntington]

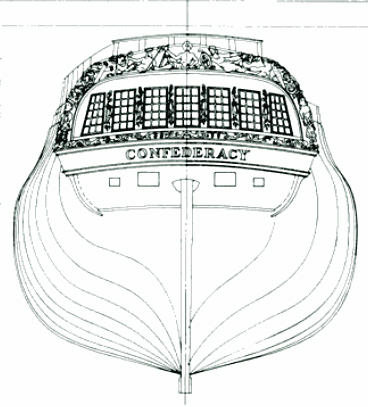

The Raleigh was the first of thirteen frigates authorized by the Continental Congress on 13 December 1775. She was designed by James K. Hackett and built by Portsmouth merchant Colonel John Langdon at Rising Castle on Badger’s Island at Kittery, Maine on the twelve mile long tidal Piscataqua River. Formed by the confluence of the Salmon Falls and Cochecho Rivers, the Piscataqua is reputed to be the third fastest flowing navigable river in the world. The Raleigh was laid down on 21 March 1776 and launched just two months later to the day on 21 May, six weeks prior to the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Although completed by midsummer, it took an additional year for Langdon “to outfit her with a hodgepodge of cannon.”55 She put to sea on 12 August 1777 under Captain Thomas Thompson who was relieved of command the following April, accused of cowardice and dereliction of duty for abandoning the Continental ship Alfred during an engagement with the British.  Appointed master of the Raleigh by the Marine Committee on 21 May 1778, Captain John Barry (1745–1803) arrived in Boston to assume command on 24 June to find a court martial underway in the great cabin.XXVI He also found the ship without a crew, cannon or supplies. Most of the ship’s cannon had been thrown overboard in the North Atlantic as former Captain Thompson fled from the British. As the Raleigh lay in port under Thompson, the officers and crew were permitted to leave the ship, looting it’s stores as they departed. Barry writes, “I found the ship had been Robb’d of a great many things.”56 Barry had enlisted less than half of the ship’s compliment by early August 1778, despite recruiting close to a hundred of the ship’s former crew. To staff the manpower shortage, the Navy Board again turned to the idled crew of the Continental Ship Trumbull still stranded in the Connecticut River. Lieutenant David Phipps of New Haven was transferred from the Trumbull, where he had been 2nd Lieutenant.XXVII Phipps came with a “large detachment of seamen” including mate Frederick Calkins within just weeks of the birth of his namesake. Phipps had been promoted to First Lieutenant with his temporary assignment with forty other Trumbull crewmen to the Warren at Providence in January of 1778. Former officers of the Raleigh returning to duty included New Hampshire natives Lieutenants Josiah Shackford and Hopley Yeaton and Captain of Marines George Jerry Osborne.XXVIII Other officers included Lieutenant of Marines Jabez Smith and Midshipmen David Porter of Massachusetts, Jesse Jacocks and Matthew Clarkson of Philadephia, Clarkson having been previously acquainted with Barry during his service on the Delaware.XXIX The pension record of Edmund Pratt identifies other commissioned and warrant officers on board the Raleigh including; Sailing Master Stephen Porter, Captain of Marines Hosmer, purser John Carr, Boatswain Celio Parker, Surgeon Gagen and Surgeon’s Mates Dorsey and John Plumb.57 Filling out the Raleigh’s compliment of 235 men were “fifty of General Burgoyne’s soldiers” serving as marines.58 Although the list of officers and crew on board the frigate Raleigh when she sailed from the Piscataqua River on 12 August 1777 and also those on board at L’Orient, France on 22 January 1778 is widely circulated, a crew list for this final and fatal cruise of the Raleigh is not known to be extant.

Appointed master of the Raleigh by the Marine Committee on 21 May 1778, Captain John Barry (1745–1803) arrived in Boston to assume command on 24 June to find a court martial underway in the great cabin.XXVI He also found the ship without a crew, cannon or supplies. Most of the ship’s cannon had been thrown overboard in the North Atlantic as former Captain Thompson fled from the British. As the Raleigh lay in port under Thompson, the officers and crew were permitted to leave the ship, looting it’s stores as they departed. Barry writes, “I found the ship had been Robb’d of a great many things.”56 Barry had enlisted less than half of the ship’s compliment by early August 1778, despite recruiting close to a hundred of the ship’s former crew. To staff the manpower shortage, the Navy Board again turned to the idled crew of the Continental Ship Trumbull still stranded in the Connecticut River. Lieutenant David Phipps of New Haven was transferred from the Trumbull, where he had been 2nd Lieutenant.XXVII Phipps came with a “large detachment of seamen” including mate Frederick Calkins within just weeks of the birth of his namesake. Phipps had been promoted to First Lieutenant with his temporary assignment with forty other Trumbull crewmen to the Warren at Providence in January of 1778. Former officers of the Raleigh returning to duty included New Hampshire natives Lieutenants Josiah Shackford and Hopley Yeaton and Captain of Marines George Jerry Osborne.XXVIII Other officers included Lieutenant of Marines Jabez Smith and Midshipmen David Porter of Massachusetts, Jesse Jacocks and Matthew Clarkson of Philadephia, Clarkson having been previously acquainted with Barry during his service on the Delaware.XXIX The pension record of Edmund Pratt identifies other commissioned and warrant officers on board the Raleigh including; Sailing Master Stephen Porter, Captain of Marines Hosmer, purser John Carr, Boatswain Celio Parker, Surgeon Gagen and Surgeon’s Mates Dorsey and John Plumb.57 Filling out the Raleigh’s compliment of 235 men were “fifty of General Burgoyne’s soldiers” serving as marines.58 Although the list of officers and crew on board the frigate Raleigh when she sailed from the Piscataqua River on 12 August 1777 and also those on board at L’Orient, France on 22 January 1778 is widely circulated, a crew list for this final and fatal cruise of the Raleigh is not known to be extant.

Captain John Barry was arguably the best commander of the fledgling Continental Navy and his many successes led to future claim on the title “Father of the American Navy.” Upon his arrival, Navy Board member James Warren confided to his friend Samuel Adams that the Marine Committee had “appointed a Good one.”59 In command of the brig Lexington in early 1776, Captain John Barry had captured the very first English prize taken in to the port of Philadelphia, HBMS Edward. Prior to commanding the Raleigh, Barry was appointed to command the 36-gun Continental frigate Effingham. With the ship still under construction, Captain Barry temporarily volunteered his services to the Army. The Effingham was scuttled when the British took Philadelphia, leaving Barry without his command and directing a flotilla of small craft and gunboats operating on the Delaware River. On 10 September 1778, Captain Barry received orders to cruise off of North Carolina specifically to intercept and destroy “certain armed Vessels fitted out by the Goodriches.” The Raleigh represented John Barry’s return to sea and Frederick Calkins was certainly at ease sailing out of Boston with the successful captain as the full length whiskered figure of Sir Walter Raleigh on the bow of this “fast sailer” turned for Portsmouth, VA at dawn on Friday 25 September 1778 in convoy with brig and sloop. With a tonnage of 697, gun deck length of 131 feet 5 inches, beam of 34 feet 5 inches, depth of eleven feet 3 inches and 32 guns, twenty-six 12-pounders and six 6-pounders; the Raleigh was the largest ship on which Calkins had yet served during the war.

Just six hours into the cruise, the reality of war would change Frederick Calkins’ life forever. Although surely acquainted with the regularity of death and crisis acquired through sixteen years of experience at sea and perhaps even familiar with the excesses of man’s violent inhumanity to man- Calkins could not have been entirely prepared for what was to happen next. Barry’s own account describes best what happened soon after the pilot was dismissed just six hours into the cruise, “At noon two sail were sighted at a distance of fifteen miles to the southeast. The Raleigh hauled to the north, and the strange vessels, which were the British fifty-gun ship Experiment and the Unicorn of twenty-two guns, following in pursuit.”Upon sighting the Experiment, a large “two decker” warship, Barry ordered the merchant vessels back to port. The chase continued until dark on the 25th with Barry noting the British ships “to all appearance gained nothing of us the whole day.” The following day, on Saturday 26 September the pursuers were sighted at seven o’clock in the morning. About four in the afternoon the Raleigh having been shadowed astern all day, the captain “lost sight of the said Vessels…Thinking they had quitted Chasing of us as I could not perceive they gained anything the whole time.” Calkins and the crew tensely stood at battle stations all day preparing for combat as Barry notes, “the Ship being ready for Action and Men at their Quarters from the first of their Chasing us.”60

“The chase continued nearly sixty hours before a shot was fired, off the coast of Maine. On the morning of (Sunday) September 27 the ships were not in sight, but reappeared about half-past nine in the forenoon. The wind blew fresh from the west, and the Raleigh, running off at a speed of eleven knots, drew away from her pursuers, but in the afternoon, the wind having diminished again, the Unicorn gained on her.” Barry decided to engage the smaller frigate Unicorn as “I found we were a Match for her.” “Give him a gun” Barry commanded as the ships drew within a quarter mile of each other as the sun began to set. 61 In classic understatement, Captain Barry describes the intensity of the seven hour long sea battle as “the engagement being very warm.”

The published narrative of two of Raleigh’s officers including Captain of Marines George Jerry Osborne details the action, “Our ship being cleared for action and men at their quarters, about five P.M. coursed the headmost ship, to windward athwart her fore foot, on which we hoisted our colours, hauled up the mizzen sail and took in the stay sails; and immediately the enemy hoisted St. George’s ensign. She appearing to be pierced for twenty-eight guns, we gave her a broadside, which she returned; the enemy then tacked and came up under our lee quarter and the second broadside she gave us, to our unspeakable grief, carried away our fore top-mast and mizzen top-gallant-mast. He renewed the action with fresh vigor and we, notwithstanding our misfortune, having in a great measure lost command of our ship, were determined for victory.” With no defenses and while the crew feverishly worked to clear the deck of wreckage while under fire, the Unicorn’s unrelenting broadsides inflicted most of Raleigh’s twenty-five casualties. The Raleigh’s officers’ account continues, “He then shot ahead of us and bore away to leeward. By this time we had our ship cleared of the wreck. The enemy plied his broadsides briskly, which we returned as brisk; we perceiving that his intentions were to thwart us, we bore away to prevent his raking us, and if possible, to lay him aboard, which he doubtless perceived and having the full command of his ship, prevented us by sheering off and dropping astern, keeping his station on our weather quarter. Night coming on we perceived the sternmost ship (the Experiment) gaining on us very fast, and being much disabled in our sails, masts and rigging and having no possible view of escaping, Capt. Barry thought it most prudent, with the advice of his officers, to wear ship and stand for the shore, if possible to prevent the ship’s falling into the enemy’s hands by running her on shore. The engagement continuing very warm, about twelve midnight saw the land bearing N.N.E. two points under our bow. The enemy, after an engagement of seven hours, thought proper to sheer off and wait for his consort, they showing and answering false fires to each other.”62 The Experiment soon came up and joined in the fire, and the British tried to cut off the Raleigh from the shore. “Encouraged by our brave commander, we were determined not to strike. After receiving three broadsides from the large ship and the fire of the frigate on our lee quarter, our ship struck the shore, which the large ship perceiving poured in two broadsides, which was returned by us; she then hove in stays, our guns being loaded gave us a good opportunity of raking her, which we did with our whole broadside and after that she bore away and raked us likewise, and both kept up a heavy fire on each quarter, in order to make us strike to them, which we never did. After continuing their fire some time they ceased and came to anchor about a mile distant.”63

What Captain Barry did not know was the Experiment was under the command of Sir James Wallace, the same enemy who had engaged him in the Delaware six months prior. Wallace and the Unicorn’s Captain John Ford were apprised of the identity of the Raleigh’s commander and were determined for victory. The British perspective of the engagement is detailed in the Experiment’s log. At quarter before six P.M. on the 27th, the “Unicorn came to close Action with the Chace, the first Broadside carried away the Enemys foretopmast and Main top-gallant Mast, at 7 a violent fireing on board both Ships, 1/2 past 9 the fireing ceased 1/2 an Hour, on which we fired several Signal Guns & was answered by the Unicorn with Lights & false Fires bearing N 1/2 E 3 miles, at 10 the Unicorn still in Action, at 11 spoke her & found the chace close by her, soon after got alongside the Chace, she gave us a Broadside & we riturned it, she then run upon the Shore, we being close to the Rocks, tacked & Anchored about 1/2 a Gun Shott from her, as did the Unicorn in 20 fathoms Water.”64

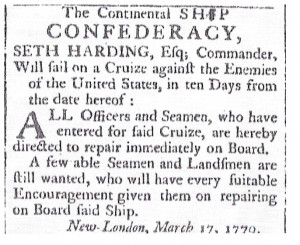

Responding to the dire circumstances enveloping the Raleigh, Captain Barry advised First Lieutenant Phipps of his plans, “Damn,em they’ll not get this Frigate…I’ll run her ashore and burn her.”65 The naval battle continued to rage after midnight into the early morning hours of Monday 28 September, providing no opportunity for the Americans to escape. Finally, as the first hand accounts describe, the Raleigh’s pierced main topsail drove the ship aground as the four stern guns continued a defensive cannonade. To Barry’s “great Grief” the Raleigh had been grounded on a rocky island near Penobscot Bay. Although named as Fox Island in the pension records of seaman James Cassel66 and marine Edmund Pratt,67 called Seal Island by the British, but surmised to be Wooden Ball Island- its identity is still not known with certainty as not one of the ship’s experienced mariners recognized the location. Immediately Barry proceeded to land his crew, intending to destroy his ship. Barry writes, “As soon as the firing was over I thought it most prudent to get the Boats out in order to save what Men I could, it then being between one and two O’Clock Monday A.M. And not a Man on Board knew what Island we were on or how far it was from the Main.”68 Within two hours, all 220 surviving crew were silently evacuated from the ship to the island, leaving fifteen presumed dead behind. When it became clear that he wouldn’t be able to retrieve the Raleigh’s cannon to defend the island, Barry divided his men into four groups. Twenty-three of the crew would return to the ship under the command of the Sailing Master with Midshipman Jesse Jacocks and scuttle her by lighting fires before escaping in one of the three longboats. Twenty-four men including the ten wounded would attempt escape to the mainland in each of the other two remaining boats. Captain Barry and Captain of Marines Osborne would command one with Lieutenants Shackford and Yeaton commanding the other. First Lieutenant David Phipps with Marine Lieutenant Jabez Smith and the remaining 132 men including most of the midshipmen and warrant officers would stay on the island awaiting rescue.69 Either through negligence or treachery the combustibles prepared for firing the ship were not ignited. Barry was convinced that Midshipman Jacocks, who did not return with the Sailing Master’s escape boat, foiled Barry’s plan to scuttle the ship. Others suggest an impressed English seaman was responsible and struck the Continental colors when the British fired on the ship in the morning. The accusation that Jacocks was a traitor is not consistent with his posting immediately thereafter on the Confederacy supervising the rigging of the ship as ranking midshipman. Negligence perhaps better describes his role as well as his posting as first master’s mate when the Confederacy put to sea.XXX

The Experiment’s log records, “at 5 A.M. the Enemy still on shore on a small barren Island called Seal Island, the Rebel Colours still hoisted, at 7 weighed and Anchored near her, fired several Guns & hoisted out all our Boats, Manned & Armed, sent a Boat ahead with a Flag of Truce to offer them Quarters, on discovering which she hawled down her Colours, her first Lieutenant and One Hundred & thirty-three Men were got ashore on the Island, but surrendered on a Summons by Truce.”70 Thirteen of the crew of the Raleigh escaped detection on the island to be reunited with Barry, resulting in a total of eighty-five who evaded British capture. The British soon took possession of the frigate and made prisoners of those of her crew who remained behind. The Raleigh lost twenty-five killed and wounded while the Unicorn saw ten killed and many wounded with severe damage to her hull and rigging. The pension record of Edmund Pratt recounts that early in the morning of his capture, Barry and the boats rowed in sight of those stranded on the island with the intent to take them off, however at that moment, a British party came up and took them prisoner. Pratt recalls, “Captain Barry seeing this and knowing that he could render us no service, waved his hat to us, as we supposed, in token that he wished us a better fate and retired.” Leaving the wounded in the care of the ship’s surgeon, Captain Barry with the balance of his crew who escaped, rowed their way back to Boston where they arrived two weeks later on Wednesday 7 October 1778. Captain of Marines Osborne and another officer suspected to be Lieutenant Thomas Vaughn would recount the naval battle in the Boston paper for news hungry readers. Captain Barry finishes his accounting of the engagement, “about 11 O’Clock A.M. About 140 of our Men were taken Prisoners and about 3 P.M. They got the Ship off… The reason I could not tell how many of our Men were made Prisoners was because there was no return of the kill’d on Board.”71 At high tide on 28 September, the British refloated the Raleigh and after repairs took her into the Royal Navy as the HBMS Raleigh. As a British vessel, she participated in the capture of Charleston, SC in May 1780. She was decommissioned at Portsmouth, England on 10 June 1781 and was sold in July 1783. Despite the loss of the Raleigh, Captain John Barry’s reputation was not impugned as he was “Honestly acquitted” by a court of inquiry.